Ήταν γύρω στα 1930 όταν ο Νίκος Μπόϊκος (ο Μπιτσιτής) συγκέντρωνε τα παιδιά του δημοτικού και πηγαίνανε στο γυμνό μικρό νησί του Αϊ Νικόλα ακριβώς απέναντι από το λιμάνι του Γάιου και φυτεύανε δέντρα. Το βράδυ, όπως κάθε βράδυ, γέμιζε με λάδι τα λαδοφάναρα στην παραλία. Σήμερα τα λαδοφάναρα έγιναν ηλεκτρικά και τα μικρά δεντράκια ένα υπέροχο πευκοδάσος που στην κορυφή του κρύβει το Κάστρο που έχτισε ο Αδάμ ΙΙ’ Σαν Ιππόλυτος το 1423. Εκεί και η μπαρουταποθήκη, n ενετική δεξαμενή, το παρατηρητήριο και τα κανόνια. Εδώ, και δύο μικρές εκκλησίες, ο Αι Νικόλας και ο Αι Ιωάννης.

Πηγή : www.healthyliving.gr

Τον 11ο αιώνα και στις αρχές του 12ου το νησί το είχαν οι Νορμανδοί της Σικελίας. Μετά τους Νορμανδούς, έγινε για πολύ καιρό λημέρι πειρατών. Το 1215 έγινε κτήση του Δεσποτάτου της Ηπείρου. Το 1259 θα είναι μεταξύ των εδαφών που θα πάρει προίκα από τον πεθερό του, τον Δεσπότη Ηπείρου Μιχαήλ Β’, ο Μανφρέδος της Σικελίας. Το 1267, μετά τον θάνατο του Μανφρέδου, θα γίνει κτήση του Ανδηγαυού βασιλιά της Νάπολης Καρόλου Α’ (Charles d’ Anjou).

Το 1374 οι Παξοί ήταν ανάμεσα στα εδάφη που πήρε κληρονομιά από τον πρίγκιπα Φίλιππο Β’ του Τάραντα ο Ιάκωβος του Μπω (Jacques des Baux ή Giacomo Del Balzo), γιος της αδερφής του Μαργαρίτας των Ανζού, που κληρονόμησε τους τίτλους του πρίγκιπα του Τάραντα, του πρίγκιπα της Αχαΐας και του Λατίνου αυτοκράτορα της Κωνσταντινούπολης. Όμως η βασίλισσα της Νάπολης Ιωάννα Α’ του έφαγε την κληρονομιά, και ο Ιάκωβος του Μπω κατέφυγε για λίγο στην Κέρκυρα, που συμπεριλαμβανόταν στην κληρονομιά του Φιλίππου του Τάραντα.

Το 1381, μετά την εκθρόνιση της βασίλισσας Ιωάννας της Νάπολης, ο Ιάκωβος του Μπω διεκδίκησε τα δικαιώματά του στην κληρονομιά. Με την υποστήριξη κάποιων βαρώνων της Κέρκυρας όπως του Αδάμ Σαν Ιππόλυτο, προσέλαβε τη μισθοφορική εταιρεία των Ναβαρραίων και κατόρθωσε να αποκτήσει την εξουσία στην Κέρκυρα και στη γύρω περιοχή (Βουθρωτό και Παξοί). Στη συνέχεια ο Ιάκωβος ετοιμάστηκε να εκστρατεύσει με τους Ναβαρραίους στην Πελοπόννησο για να κατοχυρώσει μια άλλη κληρονομιά του, το Πριγκιπάτο της Αχαΐας.

Λίγο πριν φύγει, παραχώρησε με συμβολαιογραφική πράξη της 26 Νοεμβρίου του 1381 τους Παξούς στον Ενετό Αδάμ Σαν Ιππόλυτο (Adam San Ippolito) που τον είχε βοηθήσει. Ως τότε οι Παξοί ήταν φέουδο του Βερονέζου Φίλιππου Μαλέρβα, ο οποίος είχε το αξίωμα του καπετάνου της Κέρκυρας και που προφανώς είχε εναντιωθεί στη διεκδίκηση των νησιών από το Ιάκωβο. Πιθανόν ο Σαν Ιππόλυτο κατέβαλε και κάποιο ποσό στον Ιάκωβο του Μπω που χρειαζόταν λεφτά για την εκστρατεία του στον Μοριά.

Το 1383, μετά τον θάνατο τού Ιακώβου του Μπω (ίσως και από πιο πριν), οι Κερκυραίοι βαρώνοι (πρωτοστατούντος μάλιστα του Σαν Ιππόλυτο) έδιωξαν τη φρουρά των αγροίκων και αχώνευτων Ναβαρραίων από το φρούριο, και το νησί επανήλθε στο βασίλειο της Νάπολης.

Το 1386 η Κέρκυρα καταλαμβάνεται από τους Ενετούς και οι Παξοί γίνονται κτήση της Βενετίας. Ο φεουδάρχης Σαν Ιππόλυτο όντας Ενετός διατηρεί χωρίς πρόβλημα την ιδιοκτησία του νησιού. Η ενετοκρατία στο νησί θα κρατήσει μέχρι το τέλος της Γαληνοτάτης Δημοκρατίας της Βενετίας το 1797.

Τον πρώτο ενετό κύρη του νησιού διαδέχτηκε ο ανιψιός του Αδάμ Β’ Σαν Ιππόλυτο ο οποίος το 1423 ζήτησε και πήρε από την Βενετική Γερουσία την άδεια να χτίσει με δικά του έξοδα το κάστρο στη νησίδα του Αγίου Νικολάου για την προστασία του νησιού από τους πειρατές.

Η ύπαρξη του κάστρου καθώς και του κάστρου του Διαλέτου στη Λάκκα (που δεν σώζεται) εξασφάλισαν την ηρεμία στο νησί και ακολούθησε μια μακρά περίοδος ευημερίας. Από την αρχή της ενετικής κυριαρχίας φυτεύτηκαν πολλά ελαιόδεντρα στο νησί που έτσι εξελίχθηκε σε ελαιοπαραγωγικό κέντρο.

Τον Αδάμ Β’ διαδέχτηκε η αδελφή του Λουκεντία, που παντρεύτηκε το Ριχάρδο Αλταβίλλα, έναν από τους βαρώνους της Κέρκυρας. Το 1513 η οικογένεια Αλταβίλλα πούλησε το νησί στον Ιωάννη Αβράμη αντί 3600 δουκάτων, με την υποχρέωση να πληρώνει 100 δουκάτα το χρόνο στους Αλταβίλλα και τους κληρονόμους του. Επειδή n ο Αβράμης αναγκάστηκε να επιβάλλει βαριά φορολογία, πολλές οικογένειες από τους Παξούς κατέφυγαν στην Ήπειρο, στους Τούρκους.

Τον Σεπτέμβριο του 1537 ο Τούρκος ναύαρχος/πειρατής Μαρμπαρόσσα, μετά την αποτυχία του εναντίον της Κέρκυρας, έκανε επιδρομή στους Παξούς και δεν άφησε τίποτα όρθιο. Το 1571 έγινε νέα καταστροφή από τους Τούρκους και το νησί ερήμωσε. Όσοι γλύτωσαν έφυγαν και εγκαταστάθηκαν από τους Ενετούς στα Διαπόντια νησιά.

Οι Ενετοί αποχώρησαν από τους Παξούς το 1797. Μετά ήρθαν για λίγο οι Γάλλοι, οι Ρώσοι και μετά πάλι οι Γάλλοι.

Το 1814, οι Άγγλοι έγιναν κύριοι όλων των Επτανήσων, και στους Παξούς πήραν το φρούριο από τους Γάλλους χωρίς να δοθεί μάχη (αν και τα προηγούμενα χρόνια είχαν συμβεί αιματηρά επεισόδια μεταξύ ντόπιων και Γάλλων). Μάλιστα στην εκστρατευτική δύναμη των Άγγλων συμμετείχε ως ταγματάρχης ο Θεόδωρος Κολοκοτρώνης με διοικητή τον φιλέλληνα Ριχάρδο Τσωρτς (Sir Richard Church).

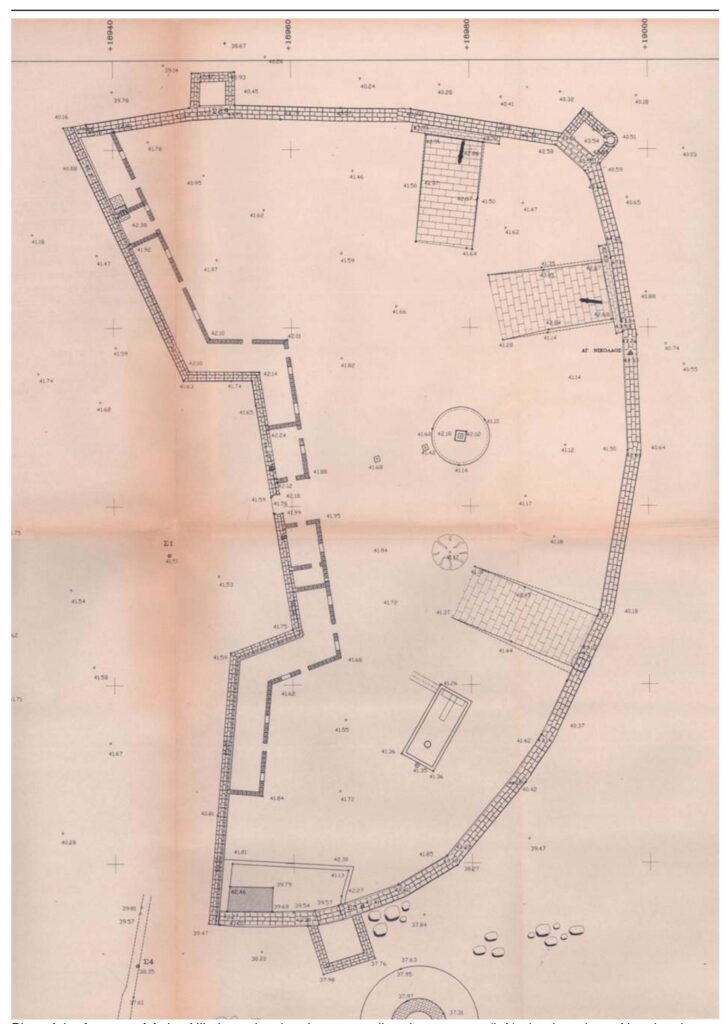

Δομικά, Αρχιτεκτονικά, Οχυρωματικά Στοιχεία

Το νησί σήμερα είναι ακατοίκητο. Από το κάστρο σώζεται μέρος των τειχών, η μπαρουταποθήκη, η ενετική δεξαμενή, το παρατηρητήριο και μερικά κανόνια. Υπάρχουν και δύο μικρές εκκλησίες, ο Αϊ-Νικόλας και ο Αϊ-Ιωάννης.

Μέχρι τη δεκαετία του 1930 στο νησί δεν υπήρχε βλάστηση. Μετά δενδροφυτεύθηκε, με αποτέλεσμα το κάστρο να μη διακρίνεται πλέον εύκολα.

www.kastra.eu

Beckmann, E. Beckmann, Edward. 2021. “Serene Speculations (Or Thoughts On The Origins Of A Venetian Defence Work In The Ionian Islands”. Academia.Edu

Serene Speculations (or thoughts on the Origins of a Venetian

Defence Work in the Ionian Islands). By E. Paul Beckmann.

The Fortress of Agios Nikolaos, Paxoi, Greece.

A recent holiday in Corfu (Kerkyra) and Paxos (Paxoi – plural being several islands), found me doing

my usual rounds of local castles and fortresses. In Paxoi, on the summit of the island of Agios

Nikolaos (St Nicholas), one of two small islands sheltering the harbour of the capital of Paxoi, Gaios,

stand the remains of the castle of Agios Nikolaos. At first sight, as the visitor approaches from the

south, the view is of a fairly conventional medieval wall, but as the visitor progresses round to the

west, towards the main entrance he is suddenly struck by the fact that this is a very peculiar castle

indeed. The island was extensively planted in the 1930s, this now mature planting is carefully

protected by the Paxoi Community and visiting the island has to be authorised by the local council.

This is because of the risk of fire; so careful has the council been that it has established a series of fire

hydrants and fixed pipes to deal with any outbreaks. On the negative side, the surrounding planting

now almost entirely obscures the views both to and from the castle remains.

The fortress, or more properly castle in its original form, appears to have been originally a roughly

ovoid shell keep, constructed c. 1432, with the permission of the Venetian authorities, by the Venetian

Baron, Adam San Hippolito for protection of the population against Ottoman and other pirates. On the

perimeter of this wall there are three square turrets, two on the north side of the structure and one on

the south side, reputedly retained post-Hellenic towers, which stand externally to the circuit walls.

The castle is built from local limestone rubble with some dressed stone details to lintels and quoins,

but is essentially a dry stone, rubble-filled double-skinned wall at least 2m thick at the base, currently

standing some 2m high and possibly 3m high originally. The original single arched entrance gate from

the south was via a sunken roadway which ran inside the wall to the west. One of the turrets stands

adjacent to the original main gate, but this gate was later blocked. This was possibly due to the

construction of a windmill and surrounding threshing floor immediately outside the gate. It is alleged

that the gate was blocked to prevent fraternisation between locals and the garrison, but it is surely

more likely that the security of the gate was compromised by the windmill’s construction.

The construction of the windmill would have ensured that all the Paxiot community would have to

visit the castle to have their corn ground and of course that the Venetian Governor of the Island,

presumably based in the castle, would be able both to levy taxes and/or take a portion of the grain to

storage for the use of the Venetian garrison and emergencies.

In the early C16th, possibly but extremely doubtfully, as early as c.1510i, the castle was apparently

remodelled, the entire western half of the circuit wall being demolished and the remaining ends of the

wall being built with a very short straight section to meet the corners of the new work, which

effectively bisected the original fortress. The new walls, being taller than the existing walls, have very

short, solid, turret-like returns at either end, pierced for arquebus fire as the rest of the new walls. This

newer, mortared, coursed stone rubble western front to the castle has a recessed section of wall with a

main gate in the centre and is flanked on either side by two demi-bastions with near right-angled

flanks. The work has been studied at some length by the distinguished Architect, Robert M. Veneriii

who has a residence on the main island and who wrote a paper on the fortress for a PanIonian

Congress held in Paxoi in 2010. Robert does think that the western wall is perhaps an experimental

work but is clearly unfinished. He also thinks that the design was heavily influenced by Leonardo da

Vinci’s ideas and was possibly designed by Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane.

At intervals along the ‘new’ curtain wall are brick-lined embrasures, set only 1.5m or so above

external ground level. The arched embrasures are approximately 1m wide on the exterior face of the

wall and taper to approximately 600mm wide in the inner face of the wall – easily accessible by

someone determined to climb in. There is a gun embrasure in the centre of each of the flanking walls,

but these embrasures do not precisely align with the opposite bastion flanks, which combined with the

low setting of the embrasures, suggests some fallibility in the translation of the design to the

construction. More interestingly, the walls of the new work are pierced with one hundred and twenty

six arquebus slots approximately 900mm apart, set at least 2.5m above ground level with a brick

stringer course both above and below the slots. Several of these arquebus slots are set directly over the

gun embrasures, which would surely have caused some operational difficulties. Some of these slots,

particularly at the south-west end of the wall, are not ‘centred’ but slanted to the south-west,

suggesting that at the time of construction, there was a perceived threat from this angle. Checking on

the inside of the bastion wall, there are a number of holes suggestive of a timber fighting platform

carrying both light guns and arquebusiers. It seems entirely possible that this fighting platform could

have had two floors, the upper carrying arquebusiers to fire over the top of the wall. However, there is

little evidence to support this.

What appears more likely is that the ‘fighting platform’ was, very unusually, a suspended floor in the

buildings behind the wall. Robert Veneri has looked at the idea that a second ‘floor’ of fighting

platform was used by arquebusiers to fire through the firing slots while lying prone; this would leave a

‘gun-deck’ below. The problem with this is that it is entirely impractical; arquebusiers would not have

been able to reload without standing up. This therefore means that it is most likely that the firing slots

for arquebusiers were for men stood on the same deck or floor as the cannon, with obvious risks and

difficulties.

The guns that this fortification carried must have been fairly light, since they only faced across the

plateau in front of the ramparts and there is no indication of any contemporary heavier guns being

mounted on the walls elsewhere. These guns could never have fired down at harbour and channel

below because of the flat plateau in front – the former interior of the castle. At the elevation of the

fortress, it would have been fairly safe against the long (and low-trajectory) guns carried by the galley

fleets of such Ottoman Admirals as the famous corsair Barbarossa (born in Lesbos). The conformation

of the structure and its relative weakness appears to confirm that original function of this fortress was

a place of refuge for the local population and is further emphasised by its lack of heavy guns but

greater number of loopholes for arquebusiers.

The primary armament of the western wall would probably have been a number of ‘Falconets’ light

cannon of up to 5cms bore and possibly 120cms long, originally developed for use at sea. Given the

location of the guns in the western wall and their available targets it is almost certain that they would

have primarily have fired grapeshot as an anti-personnel weapon, since they could never have

depressed far enough to fire on ships and were effectively hidden – by the flat ground in front – from

any other opposing forces. Larger guns would have required far more substantial gun platforms and

there are no traces of such structures or such structure as ever having existed. G. Simirisiii states

‘During the first French occupation, the incomplete bastion front was fortified with the addition of

gun loops on the middle of its side and with the final modification of its gate’. I suggest that this is

clearly not the case, as the brickwork lining to the embrasures would have been exceptionally difficult

to build into an existing wall without partially demolishing it and the brick lining the embrasure

precisely match the brick stringer courses above. This contrasts with the infill of the embrasures,

clearly built in Napoleonic or immediately post-Napoleonic times with a larger brick. Nor is it likely

that the French would have built the bastion front itself, since the location of the wall was clearly not

compatible with the weaponry of the time or the requirements to defend the seaward-facing battery

position.

Behind the wall is a discontinuous line of ruined buildings, built against the rear of the wall with an

internal wall running parallel to the outer wall. As Robert Veneri suggests, this series of structures

looks very much like a compartmentalised casemate construction, which would be consistent with the

otherwise rather thin curtain wall. The problems associated with this explanation are that the buildings

stop short of the southern tip of the bastioned wall keeping well clear of a small sunken building

reputedly used as a magazine during the French occupation. The buildings in the ‘casemates’ have

been subject to later changes, such as filling in of cannon embrasures and arquebusier slots. It is not at

all clear that the cross-walls within the casemates are all toothed in to the outer wall and most

strangely, the buildings were clearly built as ‘lean-tos’ to the rear of the perimeter wall with at least

two extant cross-walls indicating originally reasonably steeply-pitched roofs. The question this raises,

of course, is why did the builders not want to establish another line of arquebusier defences at the top

of the bastioned wall? Possibly they did, but there is no surviving indication of this. There are very

many Venetian fortresses featuring a very characteristically shaped merlon, from dates much later

than this castle. There are no extant remains of any other substantial buildings elsewhere within the

castle, suggesting that these buildings were contemporary with the bastioned west wall.

The strangest thing about this fortification is that there is no evidence of any ditches or other obstacles

in front of it. Leonardo da Vinci conducted a series of experiments in ballistics and designed a series

of tiered ramparts, each capable of firing over the other. There is no such lower rampart here and the

entire wall would have been appallingly vulnerable to even a medium-calibre artillery piece. I am

forced to conclude that not only was the ‘new’ curtain walling an experiment, but it was clearly

unfinished. One would normally expect to see a glacis in front of the wall, separated from the wall by

a ditch, the glacis usually formed from the upcast from the ditch. The extant works of the western wall

are sufficient to reasonably postulate that the works date from the period 1510 – 1585, with a

reasonable guess to the middle of that period – approximately 1545.

A key consideration in the evolution of this fortress is a look at the strategic situation of Paxoi in this

period. After the fall of Constantinople, Ottoman conquests of the various small states in present-day

Greece proceeded at a rapid rate. It was not long before the Ottoman occupation of the western and

southern coasts of Greece brought them into conflict with the Venetians, for whom their various

possessions both in the Greek islands and on the coasts of Greece were critical in maintaining their

very lucrative trade routes into the Eastern Mediterranean. Venice had come into conflict with the

Ottomans long before their conquest of Greece, when the Ottomans besieged Venetian-held

Thessaloniki in 1430 After this, there were no less than seven Venetian – Ottoman wars, of which two

approximate to the possible period of construction of the west wall of Agios Nikolaos. The key

location to the control of the Adriatic, which was regarded by the Venetians as their sea, was Kerkyra;

to enter or leave the Adriatic meant sailing past Kerkyra. Venice had possessed the island since 1386.

Agios Nikolaos in Paxoi was, of course, part of the great chain of Venetian fortresses which run

around the coasts of Greece. Each fortress had a triple function, first as a secure base from which the

Venetians ruled the adjacent territory, secondly as a defence, where possible, of a secure anchorage

and thirdly as a place of refuge for the local population in case of attack. If the population of Paxoi

had to take refuge from corsairs or Turks in the castle, it would not be long before relief would be

despatched from the much larger garrison of Kerkyra (Corfu). A Turkish occupation of Paxoi would

not be feasible without capturing Kerkyra and although the Turks tried to take Kerkyra, they never

succeeded. In 1537 and again in 1571, both Paxoi and Kerkyra were besieged by the Turks.

In 1499, at the Battle of Zonchio, a large naval battle (in which artillery was first used extensively at

sea) took place in which the Venetians under Antonio Grimani were defeated. The Ottoman fleet

under the famous Kemal Reis, was then stationed at the Ionian island of Kefalonia until the end of the

year. In 1500, following an attack by the Venetians on Lepanto, Kemal Reis recaptured the town and

then sailed to Corfu, where he bombarded the Venetian ports. He then defeated the Venetian fleet at

Modon and after bombarding the town of Modon, went on to capture it. He also captured the town of

Coron and assaulted Voiussa and appeared off the Ionian island of Lefkada, before returing to

Istanbul (Constantinople) in November of the same year. The result of Kemal Reis’s campaign was

devastating for Venice, which had already appealed for help to the Pope. A Spanish Venetian force

under the redoubtable Gonzalvo de Cordoba retook Kephalonia by the end of the year 1500. However,

Venice was under pressure on its land frontiers as well as by sea and had to subsidise the King of

Hungary to assist in the defence of the Croatian territories of Venice. The treaty with the Hungarian

King was signed in 1501, but by 1502 Venice and the Ottomans had agreed an armistice. By 1503,

with Ottoman raids into Venetian territory in northern Italy increasing, Venice was forced to

recognise the Ottoman conquests and the war ended.

In 1537 the Ottoman Sultan, Sulieman the Magnificent, declared war upon Venice and Ottoman

Admiral Barbarossa with some 25,000 troops attacked Kerkyra and Paxoi; although ultimately

unsuccessful in capturing and occupying the islands, he took 20,000 inhabitants as slaves. Spyros

Bogdanos suggests that no more than 500 people remained on Paxoi following these raids; it is

entirely possible that no inhabitants survived. Barbarossa then turned his attention to Kephallonia,

where he swept up some 13,000 islanders as slaves. Barbarossa’s siege and the ravaging of the

countryside around Kerkyra, Paxoi and Kephallonia caused massive destruction to the local economy

and the structure of the local society. Barbarossa stripped Venice of many of her Aegean possessions

and also ravaged the coast of Italy. The result was that a Christian Alliance was formed by Pope Paul

III and gave battle to Barbarossa at Preveza in 1538. The battle was a narrow Ottoman victory but any

advantage they gained was negated by a storm which scattered and sank much of their galley fleet

along the Dalmatian coast, while the Christian fleet anchored in Kerkyra. In the interim, Venetian

power was much reduced in the Ionian islands. ‘This year the Venetians possessed twenty-five

islands, each having one, two or three castles; all of which were taken; twelve of the islands were laid

under tribute, and the remaining thirteen plundered’ v The veracity of such a statement from Ottoman

historians is slightly questionable as clearly the castle at Kerkyra was not taken, but general tenor of

the statement is clearly true and admitted by the Venetians. It is alleged that Turgut Reis, the main

lieutenant and friend of Barbarossa, known in the west as ‘Dragut’ and with a formidable reputation,

used Paxoi as his base in 1538. The implication is clearly that the castle at Agios Nikolaos was taken,

since otherwise the harbour at Giaos would be untenable for Dragut’s forces. After the war, the

inhabitants of the Peloponnesian cities of Nauplion and Monemvasia, surrendered to the Ottomans in

1540, were resettled by the Venetians in the Ionian Islands as had other Venetian subjects in the

previous war. The war concluded in 1540, Venice again permanently ceding much of its territory to

the Ottomans.

Of Kerkyra, Braudel, 1972 (Vol.1 p.97) records ‘Fresne-Canaye, who was there in 1572, admired the

huge fortress towering above the little Greek town that was the island’s capital; its 700 pieces of

artillery were said to have a firing range reaching to the Albanian coast. However he was astonished

to find that the Turks had been able to lay waste the island, under its very walls, the previous year,

with 500 horsemen’vi. He should not have been so astonished, as there are clearly problems for the

Venetian defenders. The Great Siege of Malta of 1565 gives a clue as the defenders options. The

Knights of St John in Malta risked a cavalry assault on the Ottoman besiegers, achieving a local

success, but then had to withdraw back into their quarters, never to emerge again during the siege.

The Knights in Malta had been warned of the coming siege and no doubt brought cavalry in especially

to support them – for a limited period. Horses in such climates cannot survive long unless ‘salted’ –

acclimatised to subsist on local forage. Otherwise they have to depend on imported hay and fodder,

very difficult to justify shipping in if the surrounding seas are dominated by fast galleys, especially if

armaments are much more needed. Similar problems existed for the English garrison of Tangier in the

1660s. Small numbers of Venetian cavalry did exist in the islands, locally recruited Greek or

Dalmatian light horsemen, known as stradioti, (who had a formidable reputation in Western Europe at

the time) but probably not in sufficient numbers to be able to interfere with the Ottoman or other

attacks.

Venetian troops could never have defended all the shores of Kerkyra – or indeed Paxoi, since the

roads were not good enough to march troops at speed to the various landing points open to assaulting

troops with any hope of intervening. Topography would have had a large part to play in the movement

of troops, particularly mounted ones. The only option available to the Venetians was to create a series

of impregnable fortresses where the topography permitted and sit out a siege until disease, lack of

food or threats to their fleet forced the attackers to withdraw. Importantly, the fortresses of the Ionian

Islands were also built for the local population to take shelter in from Ottoman or Barbary Corsairs.

This is clearly the case with Kerkyra, with its two massive citadels in the capital, the castle of

Angellocastro to the northeast, the castles at Gardiki and Kassiopi and of course with Agios Nikolaos

in Paxoi. The great military engineer Michele Sanmicheli, (of whom more later) of Verona, who

served the Venetians, famously advised them as to how to defend the city of Udine in Friuli. First

among these recommendations was ‘that the important thing was to have a good castle; to hold the

site for Venice was more important than to defend its inhabitants’vii. This advice was clearly in the

minds of the Venetians in respect of their maritime possessions as well as the Venetian hinterland.

Mallet and Hale (1984) make a powerful point about the nature of Venetian fortresses in which ‘the

emphasis was on make-do and mend’. Expenditure on fortification was vast and on Kerkyra in

particular. For a period in 1518, the tolls from various cities within the Venetian mainland

possessions, such as Padua, Verona and Brescia were diverted to the fortification of Kerkyra, despite

the fact that Verona, for instance, had fortification needs of its own. Nor was this funding stream

unique; at various times other such diversions took place such was the perceived importance of

Kerkyra. Following the siege of Kerkyra in 1537-8 the Duke of Urbino reckoned the cost of returning

the fortress back to its original state of preparedness as over 70,000 ducats. The Venetian Senate said

of Kerkyra that it was ‘the heart and soul of this state (stato da mar) where there should always be a

reserve sufficient for all the needs of our territories south of the Gulf. They can be mobilised far more

quickly from there than from Venice to bring aid to any place that needs it.’viii In 1542 the

responsibility for the Venetian fortresses was passed to two new magistrates, the proveditores of

fortresses (in 1580 increased to three) who from that date on were responsible for the monitoring and

aiding every fortification belonging to the Republic. They were also responsible for proposing

legislation within the Venetian senate.

Who built the western wall? A number of possible designers, or perhaps more correctly, schools of

design or even families may be responsible. Christopher Duffy in ‘Siege Warfare’ (1979)ix helpfully

provides family trees for Italian engineers who carried out fortification. Selecting from this family

tree those who served the Venetian Republic provides a few engineers who may have been

responsible, but there are many other Venetian engineers not in Duffy’s family trees.

One possible early candidate for the design of the new wall, or a person who may have influenced the

new wall is Friar Giovanni Giocondo, c.1433 – 1515 of Verona, another great Renaissance polymath,

(who considered himself the disciple of Francesco Di Giorgio Martini 1439 – 1501) responsible for

the design and supervision of some of the fortifications at Treviso. Treviso was unsuccessfully

besieged by the forces of the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai (Pope Julius IInd, Louis XII of France,

Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and Ferdinand II of Aragon) in 1509 as part of their campaign

against Venice. In 1506 Fra. Giocondo was sent by the Venetians to survey the fortifications in Corfu

and the Moreax.

Yet another candidate is Michele Sanmicheli (ca. 1484-1559) who is generally credited with the

introduction to northern Italy of the Roman High Renaissance style of architecture. Another polymath,

he had a strong interest in military architecture and like Fra Giocondo, was also a disciple of

Francesco Di Giorio Martini; in 1526 he inspected papal fortifications in the Romagna in the company

of Antonio Sangallo the Younger. In 1529 he worked on the fortifications of Legnano and then on a

series of Venetian controlled cities, Verona from 1530, Chioggia from 1541 and Udine from 1543.

However, in 1535 Sanmicheli was appointed engineer of the state for lagoons and fortifications by the

Venetian State and between 1537 and 1539 he journeyed to Kerkyra, the Dalmatian coast and Crete

designing fortifications, including the encientes of Canea and Candia in Crete, designed in 1538xi. In

1535 Sanmicheli went to inspect the works being undertaken in Kerkyra by a resident military

engineer Augustin da Costelloxii, so he might have visited Paxoi. The characteristic feature of

Sanmicheli’s fortifications were massive gatehouses with rusticated stonework and heavy Doric

columns with very prominent keystones, such as at the Porta Nuova, Verona (1533-1550), the Forte di

S. Andrea a Lido, Venice (1543-1549), and the Porta Palio, Verona (1548-1557). Michele

Sanmichele’s nephew, Gian Girolamo Sanmichele also carried out work in Kerkyra as well as on the

Dalmatian coast. St. Nichola’s Fortress is one of four fortresses surrounding Šibenik and was built

between 1535 and 1550 by Gian Girolamo Sanmichele according to a design by his uncle Michelle

Sanmicheli.

Michel Sanmicheli appears to have regularly used a bastion form similar to that of the Agios Nikolaos

west front, where the bastion flanks joined the curtain wall at right angles. The dei Riformati Bastion

at Verona c. 1530 by Michel Sanmicheli is a good example, but a notable feature of this bastion is the

construction of a piazza bassa, a casemate for artillery, set low in the flank wall and designed to cover

the ditch and, of course, the face of the adjacent bastionxiii. Of course, in the case of Agios Nikolaos,

if there was no intention to provide a ditch there would have been no need to provide a piazza bassa.

Michele Sanmicheli’s emphasis on gatehouses in his fortresses is also a feature notable by its absence

at Agios Nikolaos. In fact the gateway looks incredibly weak; once any attacker is through the gate it

would have been all over with the defenders.

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger an architect and colleague of Michelle Sanmicheli built many

buildings in and around Rome, but also built fortifications, such as the bastioned enceinte around

Civitavecchia. It is not known if he visited the Ionian islands.

The Savorgnano family and their colleagues, related to Girolamo Savorgnano (1466 – 1529) a

Venetian commander who had four wives and no less than 23 sons were also very active in Venetian

service. At least three sons were actively involved in fortress construction and one, Giulio Savorgnano

(1516 – 1595) carried out works at Zara, Candia, Zante and Palmanova, all outposts of the Venetian

Empire. Evridiki Livada-Ducaxiv mentions two engineers at St George’s Castle, Kefallonia, Giacomo

di Gavardo, who died there in 1502 and his successor in 1505, Nicollo dalla Cimara. Giacomo

Coltrini xv (dates unknown, but C16th) was yet another military engineer and a noted fresco painter

who served the Venetian Republic in wide area. He died in Candia in his fifties.

Clearly, there could have been numerous military engineers responsible or partially responsible for

the works to the western wall of Agios Nikolaos and with the dearth of specific information and the

clearly incomplete works it is unlikely that we will ever be able to correctly attribute the design.

Perhaps another line of investigation given the ambiguous nature of the dating of the fortification is to

consider stylistic comparisons. Clearly, the bastioned front is incomplete and so even comparison

studies are rather limited. Most of the earlier Italian Renaissance fortresses feature either rounded

(known as orillions from their ear-lobe shape) or multi-angular bastion ends at the point where the

bastion corner intersects with the flank wall (providing cover to artillery embrasures in the flank

walls) or deeply recessed artillery embrasures close to the main curtain wall (piazza bassa).

Unfortunately for us, this style of fortification was built over a period of over one hundred and fifty

years as was the simpler, angular bastion form.

Comparison with the other Venetian fortresses of the Ionian Islands is also perhaps worth

consideration. Again, one is forcibly struck by the relative weakness of the fortress of Agios Nikolaos,

clearly compared to the truly massive fortifications of Kerkyra town (Corfu), but also to the powerful

fortification of the Castle of St George, Cephalonia. St George’s has at least two features worth

comparing with Agios Nikolaos; one is the firing slots in the parapet wall, which despite having a

strong slope at the base of the slot (enabling the firer to fire down from the great height of the Castle

of St George) are of broadly similar dimensions and distance apart. Similar slots exist in the landward

front of the Venetian Fortress of Toron (Castell Toro) at Nauplion built c.1493 – 1519xvi. A gueritte

or ‘guardiola’ stands on the perimeter wall at the extreme north-east corner of Agios Nikolaos in a

perfect position to look over the sea to the east. This has the characteristic Venetian ‘pepper-pot’

form, found in innumerable Venetian fortifications throughout the former Venetian empire.

Venetian rule in the Ionion Islands was not light and the islanders were subject to feudal laws. One of

these laws was compulsory labour and the Venetian ruthlessly enforced this. Undoubtedly, Agios

Nikolaos was constructed by local labour and it seems most likely that the original curved western

wall was used as a quarry to source the stone for the bastioned wall. This work would necessarily

have had to be completed quickly to avoid being defenceless and would have required substantial

numbers of workers on site for a considerable period, possibly causing considerable disruption to the

agricultural cycles of Paxoi.

Other impacts on the population of Paxoi included earthquakes, fire, plague and worse. As an

example, the earthquake-prone island of Kefalonia suffered from massive earthquakes in 1560, long

droughts in the years 1565-6 and raids from Sicilian pirates with Serb and Bosnian allies in 1540.

Fires are frequent throughout the Mediterranean in the summer months and some can be very

destructive, causing soil loss and of course loss of crops. There is no reason to believe that Paxoi

suffered much less than Kefalonia in the same period.

Given all the above factors and the tremendous losses of population from Ottoman raids, could it be

that the fortification was never completed through lack of resources? Could it be that some Venetian

governor decided, after a particularly devastating Ottoman raid, that a ‘state of the art’ piece of

fortification would restore the badly-damaged morale of the islanders? The fact that many of the

islanders would never have seen anything like this bastioned front might have disguised the fact that

the whole structure of the Castle of Agios Nikolaos was actually very weak. The first part of the castle

any visitor would see would be the bastioned front, an impressive sight, even if the rest of the fortress

was clearly not so special. Another alternative, one that I increasingly favour, is that possibly the

original west wall was breached during the Ottoman attacks of 1537-8, by heavy cannon* hauled up

on the mainland opposite, (to a point at the same level as the summit of the island of Agios Nikolaos

and close to the modern North Gaios bypass road) necessitating considerable reconstruction after the

castle fell, possibly under the direction of an engineer appointed by one of the Proveditors of

Fortresses just after 1542.

In 1797, following the destruction of the Venetian state by Napoleon, the Ionian Islands were

occupied by the French Republic for two years, followed by a period of Russian rule and then a

further period of French rule. In 1810, following an unsuccessful revolt by the Paxiots, the French

compelled them to carry out further improvement works to the fortress. These improvements

comprised of the construction of three internal heavy gun positions together with ramps to run the

guns up to the walls. These gun positions covered the north and especially the eastern approaches into

the anchorage of Gaios. The castle was thereby reduced in status, to become primarily a battery

position.

At the same time as the gun position works, the French appear to have set the locals to re-modelling

the existing casemates to the immediate rear of the ‘Leonardo’ wall, negating some of the defensive

value of the wall in favour of more comfortable quarters. A sunken magazine in the extreme southwest

corner of the fortress was probably refurbished at this time, but it does not appear to be a

particularly good location for such a feature.

In 1814, Major Theodoros Kolokotronis of the 2nd Regiment of Greek Light Infantry (Raised by

Major Richard Church and in British service in Corfu) landed in northern Paxos and in a short time

captured the island for the British. Kolokotronis and Church both went on to have distinguished

careers in Greek service after the liberation of Greece (Church’s career in Greek service was

considerably shorter than that of Kolokotronis). The British constructed a new cistern adjacent to the

original Venetian one, but with the added sophistication of a settling tank and filter system. Both the

British and the Venetian cisterns are in reasonable condition. A British garrison remained at the castle

until 1864, when the island and the other Ionian Islands were given to Greece.

The island was occupied by the Italians during WW2 and it is recorded that they took the ‘little

English cannons’ with them – a tragedy, because I strongly suspect they may not have been English at

all and might have helped with the dating of the castle. At least they left two of the heavy guns of the

French battery in position, one to the north and one to the west, indicating clearly how they covered

the harbour entrance.

In the 1930s the island was planted with pine trees (an idea of Mr Nikos Biokos) and these are now

mature with a partial scrub layer below. There is a serious risk of fire in the area, so that visitors have

to apply to the Town Hall for a permit before visiting. The island’s woodland is beautiful and is

treasured by the community. However, the island was bare of woodland in earlier times (Edward

Lear’s view of the island ‘Paxos – The Town and Harbour of Gaio, 1863’xvii shows almost no trees at

all) and so the setting of the castle was in plain view. I think it would be worth considering if a series

of selective views of and from the castle could be opened up, particularly views of the western wall,

but also of the gueritte to the northeast. These ‘openings’ in the woodland could be used as fire belts

and could be achieved by careful woodland management over a number of years to avoid visually

traumatic change. New plantings to the margins of the openings could include ‘fire resistant’ species

such as Oleander.

In conclusion, I have clearly raised more questions than answers, but I hope I might have focussed

some interest on what is a fascinating and frustratingly enigmatic structure. What I think has become

clear is that the Venetians appear not to think Paxoi worthy of a powerful fortress and as a result the

Paxiots were relatively disposable. Throughout this article I am struck by how much the poor Paxiot

community suffered during the period in which the castle was in use. How many Paxiots must have

been killed or ended their days as slaves within the Ottoman state, or worse as galley-slaves living a

short and ghastly life. The fortress is very much a lasting symbolic memorial to the suffering of the

community throughout the centuries and is rightly highly regarded by the modern community.

*Heavy cannon were carried in the bows of most C16th galleys, some of them extremely heavy

indeed and they were occasionally removed for land service.

i Based on the dated stone over the main gate which has ‘1510’ – or ‘1810’ crudely carved in Arabic letters in it.

I know of no Venetian structure of the C16th or C17th which does not have Latin text on its façade dating the

works.

ii Veneri, R.M. 2010 ‘La fortezza di Ag. Nicholaos a Paxi, prototipo di fortificazione alla moderna’

iii Simiris, G. ‘Castle of Agios Nikolaos in Paksi Islands’ in ‘Venetians and Knights Hospitallers’ Military

Architecture Networks’ – Athens 2002

iv Bogdanos, S. H. 2004 ‘The Saint Nicholas Island, Gaios’ Municipality of Paxos (Guide to the Castle)

v Crowley, R. 2008 ‘Empires of the Sea’ quoting Katep Celebi, ‘The History of the Maritime Wars of the Turks’

Transl. Mitchell, J. 1831

vi Lamanski, V. (referenced in Braudel 1992)

vii Mallet, M.E. 1974, ‘Mercenaries and their Masters’ quoting Joppi, V. 1861 ‘Discorso circa il fortificar della

ciita di Udine’

viii Mallet, M.E, Hale, J.R. 2006. ‘The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State; Venice c. 1400 to 1617’

quoting from SM.reg. 25, 3IV (13 May) in the Archivio di Stato, Venice.

ix Duffy, C. 1979 ‘Siege Warfare – The fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660’

x Mallet, M.E, Hale, J.R. 2006.

xi Quentin Hughes 2003 ‘A Chronology of Events related to the Turkish threat in the Mediterranean including

the sieges of Constantinople, Rhodes, Tripoli and Malta’ in ‘Fort’ Volume 31.

xii Mallet, M.E, Hale, J.R. 2006.

xiii Quentin Hughes 1974 ‘Military Architecture’

xiv Livada-Duca, E. 2000 Kefallonia; ‘The Castle of St George’ Edition of the annual cultural magazine ODYSSEIA

for Kefallonia and Ithaki (Transl. Ourania Kremmida)

xv Boni, Filippo de’ 1852. Biografia degli artisti ovvero dizionario della vita e delle opere dei pittori, degli

scultori, degli intagliatori, dei tipografi e dei musici di ogni nazione che fiorirono da’tempi più remoti sino á

nostri giorni. Seconda Edizione

xiv Andrews, K. 1953 ‘Castles of the Morea’ reprinted and revised 2006 published by The American School in

Athens and personal observation.

xv ‘Edward Lear and the Ionian Islands’ Exhibition catalogue published by the Corfu Museum of Asian Art for the

exhibition 25th May – 31st August 2012

References

Braudel, Fernand. 1992. Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press. ISBN 9780520081147.

Keen, Maurice Hugh. 1999. Medieval Warfare: A History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press. ISBN 9780198206392.

Simiris, G. ‘Castle of Agios Nikolaos in Paksi Islands’ in ‘Venetians and Knights Hospitallers’

Military Architecture Networks – Athens 2002

Duffy, C. 1979 ‘Siege Warfare – The fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660’

Mallet, M.E, Hale, J.R. 1984. ‘The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State; Venice c.

1400 to 1617’ Cambridge university Press ISBN 0521248426

academia.edu